The countercyclical capital buffer should contribute to limiting negative effects on the real economy of a future financial crisis. The buffer is to be released if stress occurs in the financial system and there is a risk of severe tightening of lending to households and firms. Therefore, the Council is ready to recommend a reduction of the buffer rate with immediate effect if such a situation occurs.

When the Council finds that the countercyclical capital buffer rate should be changed, it publishes a recommendation addressed to the Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs. The Minister is responsible for setting the buffer rate in Denmark. The Minister is required, within a period of three months, to either comply with the recommendation or present a statement explaining why the recommendation has not been complied with.

The buffer should be built up before the tide turns

It is still the assessment of the Council that risks are building up in the financial system and that the conditions exist for a further build-up of risk. The Danish economy is still in an upswing, and financial conditions are generally accommodative. The sustained low level of interest rates increases the risk of asset bubbles building up and provides an incentive for increased risk-taking. A few indicators point to slightly weaker development, but the build-up of risk has not slowed down substantially. Hence, the Council pursues its announced strategy to recommend an increase of the buffer rate in this quarter.

The buffer must be built up before financial imbalances grow too large, making the financial sector vulnerable to negative shocks. The buffer can be released if risks materialise and there are signs of a financial crisis. Releasing the buffer aims to prevent the banks and mortgage credit institutions from reducing credit supply due to capital shortfalls.

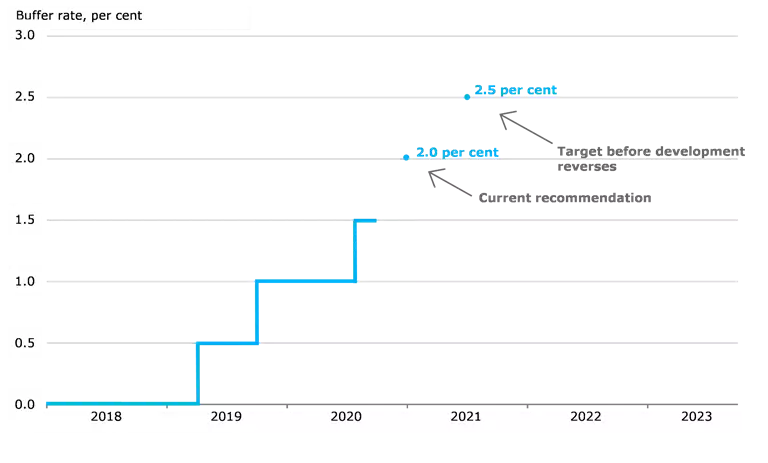

The buffer must be of a certain size to make a difference when, at some point, it becomes necessary to release it. Consequently, the Council's opinion is that, unless the risk build-up in the financial system slows down considerably, the buffer should be built up to 2.5 per cent. The gradual build-up of the buffer is illustrated in Chart 1.

The Council's assessment of the buffer rate is based on an overall assessment of financial system developments.[1] Besides a number of indicators of financial developments, the Council considers other relevant information, including other policy measures and other requirements imposed on the institutions.

| Gradual increase of the countercyclical capital buffer rate | Figure 1 |

|---|

|

| Note: The buffer rate is determined by the Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs 12 months in advance |

Risk build-up in the financial system

The Danish financial system is highly affected by international market developments. Increased risks for the global economy have resulted in stronger fluctuations and uncertainty in the financial markets during 2019. However, risk perception in the financial markets has been very low for many years. Combined with the generally very low interest rate environment, this has led to search for yield and risk-taking among financial companies, both abroad and in Denmark. Market participants expect negative money market interest rates for a long time to come, both in Denmark and in the euro area.

Several large countries' fiscal and monetary policy scope has been limited by high debt and low interest rates. This reduces their opportunities for mitigating the negative effects which may arise should risks materialise. This emphasises the importance of credit institutions (banks and mortgage credit institutions) being resilient against the effects of an international downturn.

The Danish economy is still in an upswing, and asset prices are generally high. Prices in both the housing market and the commercial property market have risen for several years, but the growth rates have flattened since mid-2018. Prices of single-family houses continue to increase moderately. Price growth for owner-occupied flats has slowed down, while the number of sales has declined. Price levels in Copenhagen are, however, still high, supported by the low interest rate environment.

The institutions show signs of higher risk appetite, although overall credit growth is moderate. In general, the institutions have built up considerable capacity for increasing lending, and credit standards have been eased for corporate customers for a prolonged period of time. Increased competition for customers may lead to lower credit quality.

The long period of low interest rates and accommodative financial conditions, combined with the economic upswing, provides a basis for further build-up of credit risk. Risks are amplified by the already high level of total credit.

The indicators in the Council's information basis have been elaborated on in Appendix A.[2] There is no mechanical relationship between the indicators and the buffer rate, given the uncertainty of measuring systemic risk developments, including that historical indicators are not necessarily adequate for indicating future developments. Consequently, the Council's assessment of the buffer rate is based on an overall assessment of the indicators in a longer-term perspective and other relevant information.

The institutions have capital to meet the requirement

With their current capitalisation, the vast majority of the credit institutions will be able to comply with a 2.0 per cent countercyclical buffer requirement.[3] The higher buffer requirement enters into force 12 months after the Minister's announcement of an increase. This gives the institutions one year to meet the requirement.

An increase of the buffer rate by 0.5 percentage point will add kr. 7 billion to the total regulatory equity requirement for Danish institutions. By comparison, earnings totalled kr. 32 billion in 2018, and the sector's excess capital adequacy totalled kr. 100 billion in mid-2019.

As a result of the higher requirement, a larger share of the institutions' balance sheets must be financed by equity. This can be achieved by retaining earnings instead of distributing them as dividends or share buy-backs. In 2018, the institutions' dividends totalled kr. 17 billion and their share buy-backs totalled kr. 10 billion. Earnings always accrue to the shareholders, irrespective of whether they are distributed or retained.

The requirement that the institutions must maintain a countercyclical capital buffer is not a "hard" requirement, meaning that institutions in breach of the requirement will not lose their banking licences. Instead, they will be required to submit a capital conservation plan to the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority, and bonus and dividend payments etc. may also be limited if they fail to comply with the combined capital buffer requirement.[4]

The countercyclical capital buffer was introduced in international regulation after the financial crisis as part of an extensive set of reforms to make the financial sector more resilient. The buffer is applied in 13 other European countries, cf. Appendix B.

The buffer is to reinforce the institutions' resilience

The countercyclical capital buffer is an instrument for strengthening the resilience of the institutions by increasing their capitalisation in periods when risks are building up in the financial system. The buffer must be built up before financial imbalances grow too large and increase the risk that a negative shock to the financial system leads to a financial crisis.

If financial stress occurs and there is a risk of severe tightening of lending, the buffer can be reduced so that capital is released. In so far as the institutions do not use the released capital for absorbing losses, it may be used for new lending or to maintain their excess capital adequacy. This helps the credit institutions to maintain a suitable level of lending in periods of stress in the financial system. In that way the buffer contributes to limiting the negative effects on the real economy.

In a situation where the Minister decides to release the buffer, this can be done with immediate effect. When the buffer rate is increased, it takes 12 months from the Minister's announcement of the decision until the institutions must comply with it.

The Council's strategy is a gradual phasing-in of the buffer. This makes it easier for the institutions to adapt to the new, higher capital requirements e.g. by retaining earnings. The Council thus expects the potential impact on lending to be limited.[5]

The buffer is primarily an instrument for strengthening the resilience of the credit institutions. It cannot be used as an instrument to manage the business cycle, either in an upswing or in a downturn. The buffer must be released if there is a risk of severe tightening of lending to households and firms, and not necessarily in an economic slowdown.

Other capital requirements

The Council also includes other policy initiatives in its considerations regarding the countercyclical buffer rate, including the phasing-in of future requirements for the institutions. At mid-2019, the vast majority of the Danish institutions had sufficient capital to meet both the buffer requirements[6] that have been phased in until 2019 and a countercyclical capital buffer of 2.0 per cent in Denmark. The countercyclical capital buffer differs from other buffer requirements in that it can be eased in times of financial stress, whereas the other requirements apply in both good and bad times.

Besides the buffer requirements, the institutions will be subject to other forthcoming requirements, including the requirement that a bank must have a certain volume of capital and debt instruments that can absorb losses in a crisis situation, known as the MREL.[7] The purpose of the MREL differs from the purpose of the countercyclical capital buffer, cf. also Appendix A.

The Danish Financial Supervisory Authority's overall assessment is that the phasing-in of the individual MRELs by 2023 will have little impact on the banks' ability to meet a countercyclical capital buffer requirement of 2.0 per cent. The Danish Financial Supervisory Authority expects the small banks to be able to meet their MRELs via their existing capital base as well as retained earnings, while the large institutions will extensively be able to meet the requirement by issuing MREL instruments.

Another future requirement is a minimum leverage ratio requirement for the institutions, to be met as from 2021 when new EU regulation enters into force. While the buffer is calculated as a ratio of risk-weighted exposures, the leverage ratio is calculated relative to unweighted exposures. The leverage ratio requirement will entail a higher capital requirement than the risk-based minimum requirement for groups with a very large share of assets with very low risk weights, such as mortgage loans. This means that, in a crisis, some systemic groups will not be able to fully use their capital buffers to absorb losses before they breach the minimum leverage requirement.

Among the forthcoming requirements for institutions are the Basel Committee's recommendations for adjustment of the capital requirements, published in December 2017. Their purpose differs from that of the countercyclical capital buffer, cf. Appendix A. The Basel Committee envisages phasing-in of the adjusted requirements from 2022 to 2027. The requirements must be adopted by the EU before they are imposed on Danish institutions.

The Council's recommendation is in compliance with current legislation.

Lars Rohde, Chairman of the Systemic Risk Council

Statements from the representatives of the ministries on the Council

"Legislation regarding the Systemic Risk Council stipulates that recommendations addressed to the government must include a statement from the representatives of the ministries on the Council. Neither the representatives of the ministries nor the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority have the right to vote on recommendations addressed to the government.

The government notes the Council's recommendation to the government to set the rate of the countercyclical capital buffer at 2 per cent with effect from 30 December 2020. The Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs will announce the government's decision on the rate of the countercyclical capital buffer for the 4th quarter of 2019 as soon as possible."

For an elaboration on the Council's information basis, see the appendix in the recommendation.

[1] Legislation allows the buffer rate to be set higher than 2.5 per cent if this is warranted by the basis for assessment.

[2] See also the Council's buffer assessment method at the Council's website www.risikoraad.dk.

[3] The institutions must meet the countercyclical capital buffer requirement with Common Equity Tier 1 capital.

[4] In addition to the countercyclical capital buffer, the combined capital buffer requirement consists of the capital conservation buffer for all institutions and a SIFI buffer for systemically important institutions, SIFIs.

[5] Danish experience shows that the increased capital requirements introduced under the international post-crisis regulation have not resulted in declining lending, cf. Brian Liltoft Andreasen and Pia Mølgaard, Capital requirements for banks – myths and facts, Danmarks Nationalbank Analysis, No. 8, June 2018.

[6] The buffer requirements comprise the capital conservation buffer for all institutions and a SIFI buffer for systemically important financial institutions, SIFIs.

[7] The MREL is a minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities. These own funds and eligible liabilities can absorb losses and recapitalise an institution in a resolution situation.