The Danish Systemic Risk Council, in cooperation with Føroya Váðaráð, the Faroese Systemic Risk Council, has prepared this analysis of requirements for the Faroese banks. The analysis is, inter alia, a follow-up on an opinion from the Faroese Risk Council received by the Danish Risk Council in March 2019. The opinion concerned thresholds for the indicators used to designate systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) in the Faroe Islands. The Danish Risk Council discussed the analysis in December 2019 and found that the current capital buffer requirements are appropriate.[1] Representatives of the Faroese Risk Council have participated in the discussions. The Danish Risk Council decided to continue working on the criteria for the designation of SIFIs in the Faroe Islands. This work has formed the basis for the recommendation 'Changing the criteria for SIFI designation in the Faroe Islands' of 4 March 2020.

The Faroe Islands pursue an independent economic policy. However, certain policy areas have not been devolved to the Faroe Islands. They include policy areas relating to the financial sector, where banks is a Danish area of responsibility. The Faroese banks are under the supervision of the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority (FSA),[2] while the Danish Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs is responsible for deciding capital buffer requirements in the Faroe Islands.

The Danish Risk Council is responsible for identifying and monitoring systemic financial risks in the Faroe Islands and can recommend macroprudential measures relating to the banks in the Faroe Islands. The Faroese Risk Council also identifies and monitors systemic financial risks, but cannot recommend macroprudential measures relating to the banks, as this is a Danish area of responsibility. The Faroese Risk Council can submit opinions to the Danish Risk Council. According to Faroese law, the opinions cannot be made public.[3]

Faroese banks, like Danish banks, are subject to a number of legislative requirements: Pillar I and II requirements, capital buffer requirements and MREL requirements. There are four capital buffers: The capital conservation buffer, the SIFI buffer, the systemic risk buffer and the countercyclical capital buffer. While the capital conservation buffer is the same for all countries, the other three buffers are determined on the basis of national conditions. The three buffers are macroprudential requirements and thus a matter for the systemic risk councils in the Faroe Islands and Denmark.

1. Summary and assessment

1.1 Capital requirements in the Faroe Islands

Capital requirements contribute to ensuring financial stability. Inadequate capitalisation increases the vulnerability of the financial sector to crises where the risk of problems in one or more institutions spreading to others. From an overall economic point of view, the costs associated with fulfilling the capital requirements for each institution and its customers must be weighed against the protection afforded against financial crises. Following the most recent financial crisis, the capital requirements have generally been tightened by international regulation in order to make the financial sector more robust.

Danish financial regulation has been implemented for the Faroe Islands by royal decree or through the implementation of special legislation.[4] As EU legislation is either implemented or directly applicable in Denmark, the rules implemented in the Faroe Islands are, in effect, the EU rules. This ensures cross-border comparability. The size of the capital buffers is determined on the basis of national conditions (except for the capital conservation buffer). The current capital buffer requirements in the Faroe Islands are based on an assessment of conditions in the Faroe Islands. The buffer requirements do not automatically follow Danish or EU requirements.

The Faroese economy is small and open and characterised by a concentrated business structure. This makes the economy vulnerable to negative shocks, which can lead to losses in the banking sector and amplify fluctuations in the real economy. Historically, the Faroese economy has experienced large fluctuations, resulting in higher levels of impairment charges in the Faroese banks than in Danish banks. Therefore, it is appropriate that capital requirements should be higher than in Denmark.

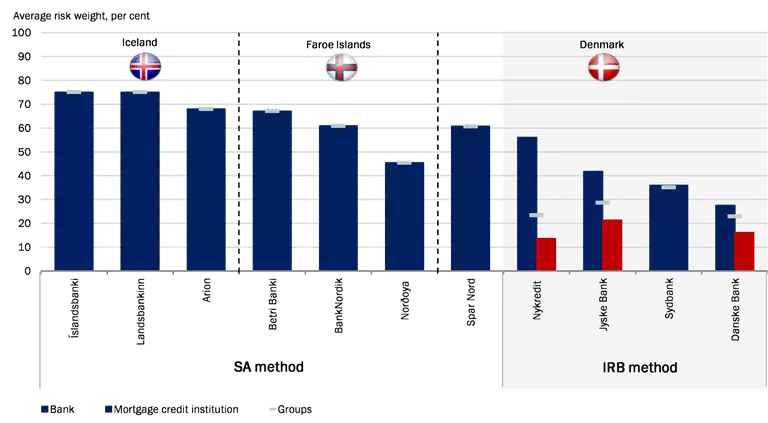

Capital requirements are calculated as a percentage of the banks' risk-weighted exposures. The average risk weights of the Faroese SIFIs are generally higher than the risk weights of the Danish SIFIs, reflecting differences both in their portfolios and in the methods used to calculate the risk weights. The Faroese SIFIs use the standardised approach (SA) to determine the risk weights, while the Danish SIFIs use internal models (IRB).[5] The difference between risk weights determined according to the SA and IRB methods will be less pronounced once the future floor requirements, i.e. the output floor, for risk weights are implemented. The output floor has been proposed by the Basel Committee and must first be implemented in the EU before being introduced for the Danish IRB institutions. A process is now under way in the EU.

Capital requirements and lending

The effect of increased capital requirements on lending by the banks depends on how the banks adjust, which depends on the economic and financial situation. It is therefore difficult to measure the effect in practice. In recent years, the capital requirements have increased in the Faroe Islands, as has total lending.[6] In the same period, there has been an economic upswing in the Faroe Islands.

The exposures of Danish banks in the Faroe Islands are low. Lending by Danish mortgage credit institutions, brokered through the Faroese banks, has increased since the beginning of 2018. One explanation may be that these mortgages require less capital, and that the Faroese banks want to reduce the share of housing loans compared to the their total lending.

1.2 SIFIs in the Faroe Islands

The Faroese banking sector can largely be seen as an independent market, which is separate from the Danish banking market. The bankruptcy of a major Faroese bank can have significant negative consequences for the Faroese economy. The systemic importance of the Faroese banks is therefore measured in relation to the Faroese economy and the Faroese banking sector.

Three out of four banks in the Faroe Islands have been designated as SIFIs. All three banks are relatively large compared to the Faroese economy. However, the smallest of the three banks – Norðoya Sparikassi – is a small bank with only 44 employees. Norðoya has sufficient common equity capital to meet the phased-in buffer requirements and a systemic risk buffer of 3 per cent in 2020. Whether Norðoya can meet a future MREL requirement based on its existing capital and earnings will depend on the level of such MREL requirement, which has not yet been decided. The Danish FSA sets the MREL requirement.

Thresholds

The thresholds for the indicators used to designate SIFIs in the Faroe Islands were originally twice as high as the ones applicable in Denmark. This should be seen in light of the fact that, measured against GDP, the Danish banking sector is about twice the size of the Faroese banking sector. For the deposits indicator, the threshold is more than twice as high, as the threshold has been reduced in Denmark, without changing the threshold for the Faroe Islands.[7]

The indicators used to designate SIFIs are calculated relative to the Faroese GDP and the Faroese banking sector. However, as the Faroese economy is quite small, even small banks can achieve SIFI status.

Assessment: The Systemic Risk Council finds that a lower limit for the absolute size of a bank should be introduced so that very small banks are not designated as SIFIs, cf. recommendation to change the criteria for SIFI designation in the Faroe Islands. In this analysis, Norðoya Sparikassi is included in charts and tables based on its current SIFI status.

SIFI requirements and MREL requirements

If a SIFI experiences difficulties, it could lead to negative repercussions for the economy. SIFIs are therefore subject to additional requirements to reduce the probability of the institutions failing and limit the negative consequences in case of their failure.

The two largest banks in the Faroe Islands are subject to a 2 per cent SIFI buffer requirement, while the requirement for Norðoya Sparikassi is 1.5 per cent of risk-weighted exposures. The SIFI buffer depends on the systemic importance of the banks. For the Faroe Islands, the systemic importance is calculated as the average of three indicators (market shares for balance sheet, lending and deposits) divided by two. For Danish SIFIs, systemic importance is calculated as an average of the three indicators.

As a non-SIFI, Norðoya Sparikassi would not have to meet the same requirements. It would no longer be subject to a SIFI buffer requirement or any of the other SIFI requirements, such as reporting and the appointment of various committees. It would still have to meet an MREL requirement[8]. The MREL requirement is determined in accordance with the preferred resolution strategy set out in the institution's resolution plan.

As far as the Faroese SIFIs are concerned, it can be seen from the Danish FSA's preliminary principles and the recent decision concerning the MREL requirement for BankNordik that the systemic risk buffer should only be included once in the MREL requirement.[9] The SIFI buffer and the capital conservation buffer are included twice, as is the case for the Danish SIFIs.[10]

The MREL requirement contributes to ensuring a resolution process without the use of government funds, and without such resolution having any significant negative impact on financial stability. Institutions can meet their MREL requirements by retaining earnings or issuing new capital and debt instruments such as shares or non-preferred senior debt.

Assessment: The systemic risk councils in both Denmark and the Faroe Islands are of the opinion that the other capital buffer requirements are currently appropriate. As regards the MREL requirements, the Danish Risk Council will annually assess whether there are indications that phasing-in of the requirements has significant negative implications for the Faroese economy. If that is the case, the Council is ready to recommend an extension of the MREL phasing-in period.

Resolution

If a non-SIFI is failing, the initial response would be to seek a market solution. This means that private solutions will be sought, including a merger with a stronger institution. If this is not possible, an orderly wind-down must be carried out, selling the good assets and transferring the rest to Finansiel Stabilitet for resolution.

A market solution can be more difficult in the Faroe Islands than in a larger economy. As the Faroese banking sector can to a very large extent be seen as an independent market, there are not a lot of banks that can take over – or buy the good assets of – a failing bank.

1.3 Systemic risk buffer and countercyclical capital buffer

The general systemic risk buffer and the countercyclical capital buffer have been implemented in the legislation of the EU and EEA countries, but levels are set by national authorities on the basis of national conditions. The buffers apply to all institutions.

The systemic risk buffer addresses structural systemic risks, while the countercyclical capital buffer addresses cyclical systemic risks. For the purpose of addressing cyclical risks, the regulatory requirement can be increased in good times and reduced in bad times, while the requirement designed to counter structural risks basically does not change over time. In practice, however, it can be difficult to make a stark distinction between cyclical and structural systemic risks.

Structural vulnerabilities are deemed to be greater in the Faroe Islands than in Denmark. A systemic risk buffer of 3 per cent therefore applies from 1 January 2020. The purpose of the buffer is to make the banks more resilient to large fluctuations in the Faroese economy.

The countercyclical capital buffer is not activated in the Faroe Islands. The buffer must be built up during periods of increasing systemic risk and released in times of crisis to support the supply of credit. The buffer is associated with advantages as well as drawbacks. One advantage is that it can be released. A drawback is that there may be resistance to increasing it in good times. Another drawback is that it is difficult to decide exactly when it should be built up and when released, especially in a small economy as the Faroese with a limited number of financial indicators. As it is difficult to measure systemic risks, the buffer cannot be set mechanically with reference to a single indicator. The assessment must therefore be based on a broad information set.

Assessment: The systemic risk councils in both Denmark and in the Faroe Islands deem the current level of the general systemic risk buffer to still be appropriate. There are currently no grounds for activating the countercyclical capital buffer in the Faroe Islands. This should be seen in light of the fact that the general systemic risk buffer increases the banks' resilience to large fluctuations in the Faroese economy. The cyclical fluctuations should therefore be pronounced for the countercyclical capital buffer to be activated.

2. Faroese banking sector

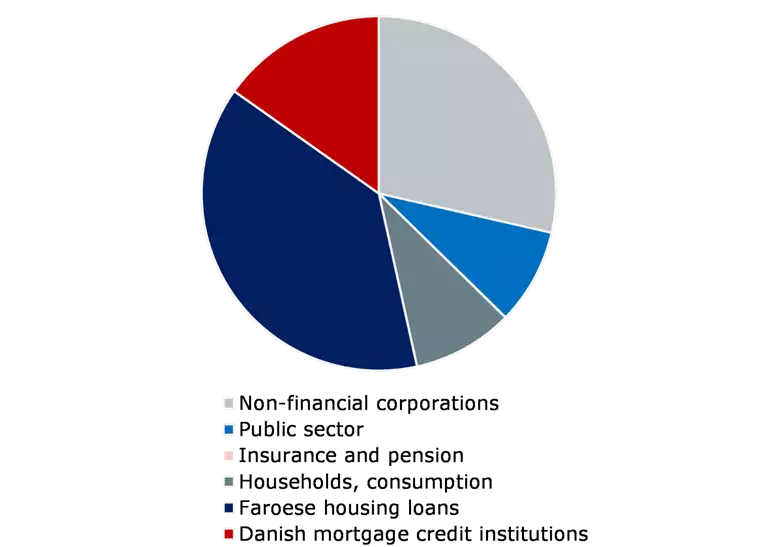

There are a total of four banks in the Faroe Islands, and their aggregate assets was about 150 per cent of the Faroe Islands' GDP in 2018. Lending by the Faroese banks accounts for most of the total lending to Faroese residents, cf. Appendix A. About half of total lending by the Faroese banks is to households, mostly in the form of housing loans, cf. Chart 1 on the left. Faroese housing loans are variable-rate bank loans.

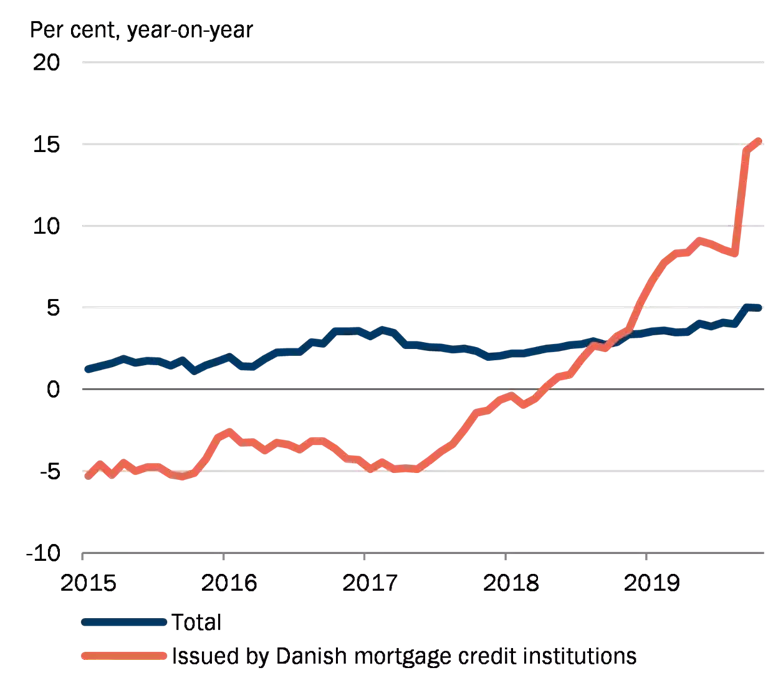

Danish mortgage lending for housing financing was introduced in the Faroe Islands in 2006 and is brokered by the Faroese banks. Terms etc. are the same as in Denmark, but contribution rates are higher. Borrowing from Danish mortgage credit institutions has increased since the beginning of 2018, cf. Chart 1, and accounts for just over a quarter of total housing financing in the Faroe Islands. 70 per cent of mortgages are variable-rate, while 30 per cent are fixed-rate.[11]

Lending by the Faroese banks to the corporate sector is especially to commerce, industry and fisheries and aquaculture, cf. Appendix A. Over the past ten years, there has been a decline in the importance of Faroese banks as a source of funding for Faroese companies. The banks account for a lower share of corporate borrowing, while there has been an increase in the share of equity funding. This development should be seen, among other things, in light of the positive economic development in the Faroe Islands.

| Loans, Faroese residents | Chart 1 |

|---|

| Distribution of loans, October 2019 |

Housing loans |

|

|

Note: MFI statistics. Lending in left-hand chart is by Faroese banks and Danish mortgage credit institutions. 'Public sector' consists of municipalities, social funds and public corporations. The State, i.e. 'Landsstyret', relies on the bond market as a source of funding. Total housing loans in the right-hand chart are from Faroese and Danish banks as well as Danish mortgage credit institutions. Latest observation in the right-hand chart is from October 2019.

Source: Landsbanki Føroya and Danmarks Nationalbank |

2.1 SIFIs in the Faroe Islands

Three of the four Faroese banks have today been designated as SIFIs based on the size of their balance sheets and market share of lending and deposits, cf. Table 1. Measured on balance sheet and number of employees, BankNordik is the largest SIFI, while Norðoya Sparikassi is the smallest SIFI.

| Characteristics of the Faroese banking sector | Table 1 |

|---|

| |

BankNordik |

Betri Banki |

Norðoya Sparikassi |

Suðuroyar Sparikassi |

SIFI indicators, per cent

- Balance sheet-to-GDP ratio (>13)

- Lending, market share (>10)

- Deposits, market share (>10)

SIFI status, 2019

Corporate structure

- Employees

- Form of incorporation

- Jurisdiction |

89

43

41

Yes

359

A/S

FO, DK, GL |

51

40

42

Yes

136

A/S

FO |

14

13

13

Yes

44

Savings bank

FO |

4

4

4

No

16

A/S

FO |

Note: The figures in brackets for the SIFI indicators indicate the thresholds for SIFI designation. The SIFI indicators are from the Danish FSA's SIFI designation in 2019.

Source: The Danish FSA and financial statements for 2018 |

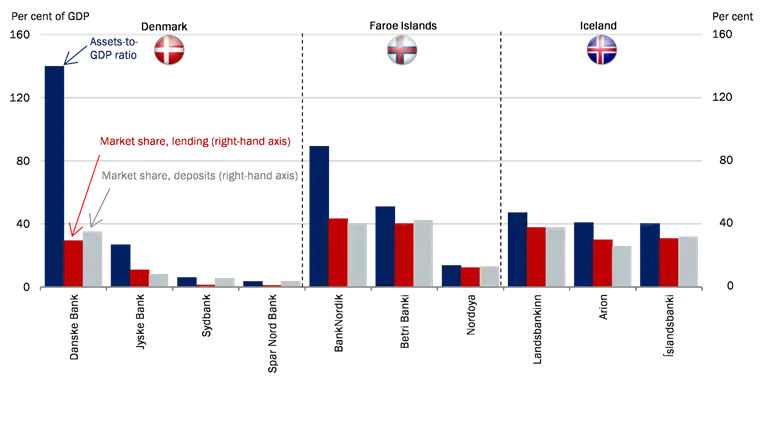

The Faroese SIFIs are small compared to the Danish SIFIs, but given the size of the Faroese economy, the Faroese banks are relatively large, especially the two largest, cf. Chart 2.

For comparative purposes, the Icelandic SIFIs are also shown in Chart 2. The Icelandic economy is very similar to the Faroese, and the Icelandic banks use the same method to calculate their risk weights, cf. section 3 below.[12]

| Size of SIFIs relative to national GDP and national sector | Chart 2 |

|---|

|

Note: Selected Danish SIFIs. For the Danish and Faroese SIFIs, the data used are data published by the Danish FSA in connection with SIFI designations for 2019. For Iceland, ratios have been calculated on the basis of MFI statistics (Seðlabanki Íslands) for end-2018.

Source: The Danish FSA and Seðlabanki Íslands. |

The designation of SIFIs under Danish, and subsequently Faroese, legislation is based on the political agreement from October 2013 (Bank Rescue Package 6). The thresholds for the indicators used to designate SIFIs were twice as high for the Faroe Islands compared to the Danish thresholds. This should be seen in light of the fact that, measured against GDP, the Danish banking sector is about twice the size of the Faroese banking sector.[13]

The designation of SIFIs in Iceland is based on guidelines from the European Banking Authority (EBA). The EBA guidelines were published in 2014 and include at least ten indicators for calculating the systemic importance of the institutions.[14] No thresholds have been defined for the individual indicators.

3. Capital buffer requirements and risk weights

Capital requirements are calculated as a percentage of the banks' risk-weighted exposures. This section provides an overview of various capital buffer requirements and methods for calculating risk-weighted exposures.

The capital buffer requirements for SIFIs in the Faroe Islands, Denmark, Greenland and Iceland are shown in Table 2. The capital conservation buffer is 2.5 per cent for all banks in all countries, while the other buffers depend on national implementation. The general systemic risk buffer and the countercyclical capital buffer are the same for all banks in that country, while the SIFI buffer is institution-specific.

| Capital buffers for Danish, Faroese, Greenlandic and Icelandic SIFIs | Table 2 |

|---|

| |

|

Buffer rate in home country |

| Per cent of risk-weighted exposures |

Capital consrevation buffer |

SIFI buffer |

Systemic risk buffer |

Countercyclical buffer |

| Danske Bank |

2.5 |

3 |

0 |

2 |

| Spar Nord |

2.5 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| Betri Banki |

2.5 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

| Banknordik |

2.5 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

| Norðoya |

2.5 |

1.5 |

3 |

0 |

| GrønlandsBANKEN |

2.5 |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

| Icelandic SIFIs |

2.5 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

Note: There are seven Danish SIFIs, see the others in Table 5 below. The systemic risk buffer applies only to domestic exposures (for the Faroe Islands and Iceland, respectively). The countercyclical buffer rates are the agreed rates in the countries (applicable from December 2020 in Denmark and February 2020 in Iceland). The institution-specific countercyclical buffer rates depend on the institution’s exposures in different countries.The three Icelandic SIFIs are subject to the same buffer requirements.

Source: European Systemic Risk Board and national authorities' websites. |

As mentioned above, the buffer requirements are calculated as a percentage of the institutions' risk-weighted exposures. The Faroese and Icelandic banks use the standardised approach (SA) to calculate their risk weights, as does the Danish SIFI Spar Nord Bank. The other Danish SIFIs use Internal Ratings Based (IRB) models to calculate their risk weights.[15]

In the SA approach, the exposures of institutions are divided into categories with internationally determined risk weights. The method is simple and transparent, but it is only adapted to the general risk associated with the various exposure types and not the actual risk of each exposure.

Institutions using the IRB method must calculate risk weights by estimating a number of key parameters for each exposure based on their own data.[16] The calculated risk weights reflect aspects such as the institution's loss history and customers' individual circumstances, e.g. income and LTV ratios. The use of IRB methods requires authorisation, and the models must be approved by the supervisory authority. Differences in risk weights can therefore be ascribable both to differences in portfolios and in calculation methods.

The IRB risk weights are typically lower than the weights calculated using the SA method.[17] However, the difference between the SA and IRB methods will decrease when the future so-called output floor is implemented, cf. Appendix B.[18] The output floor is a floor under the risk-weighted exposures and affects only IRB institutions.

In 2017, an expert group appointed by the Danish government forecast that the capital requirements of the Danish SIFIs will increase by an average of 34 per cent if the output floors and revised IRB method are introduced in accordance with the recommendations of the Basel Committee. A process is now under way in the EU prior to implementation of the Basel Committee's proposal in EU legislation.

IRB method for the exposures of Danish institutions in the Faroe Islands

Use of the IRB method for credit risk on Faroese exposures by an IRB institution is subject to authorisation by the Danish FSA. The authorisation must cover Faroese exposures. If the institution's IRB authorisation does not include Faroese exposures, the institution must apply the standardised approach to calculate the credit risk associated with its Faroese exposures. If an IRB institution wishes to transition from the SA method to the IRB method for Faroese exposures, prior approval must be obtained from the Danish FSA.

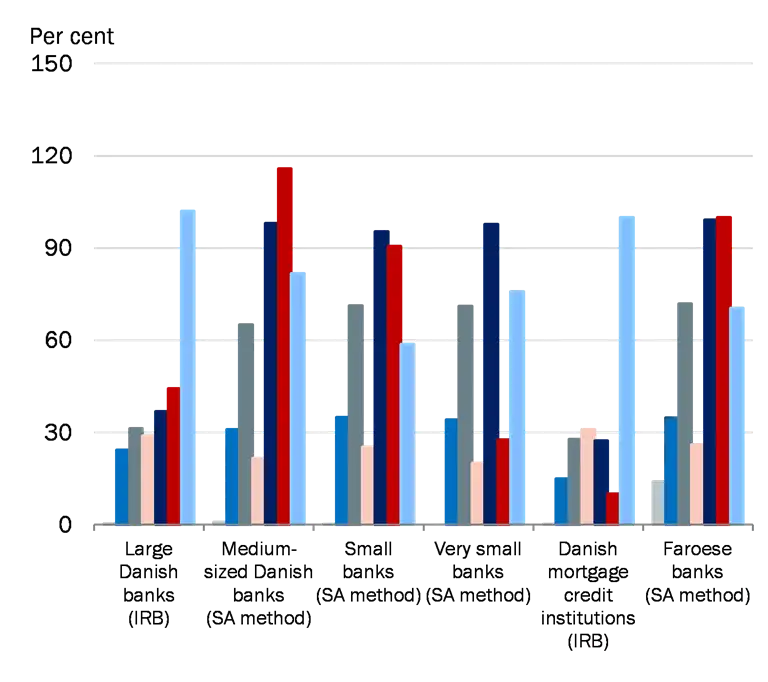

3.1 Average risk weights of banks

The average risk weight of the Faroese banks is higher than that of the large Danish banks in group 1 as a whole, but slightly lower than the risk weight of the medium-sized banks in group 2, cf. Table 3.[19]The Icelandic banks have a higher average risk weight than both the Faroese and Danish banks.

| Average risk weights of banks, Q3 2019 | Table 3 |

|---|

| |

Large

(group 1) |

Medium-sized

(group 2) |

Small

(group 3) |

Very small

(group 4) |

Faroe Islands

(group 6) |

Iceland |

| Gennemsnitlig risikovægt |

32.4 |

63.6 |

62.6 |

58.4 |

61.2 |

72.7 |

Note: The average (implicit) risk weight is the ratio between risk-weighted exposures and aggregate assets. Data for Iceland are for Q2 2019.

Soruce: The Danish FSA and financial statements of Icelandic banks. |

For the SIFIs, there are differences between individual institutions, cf. Chart 3. The average risk weights of the Faroese SIFIs are on a par with the Danish SIFI Spar Nord. The risk weights of the other Danish SIFIs – using the IRB approach – are lower, especially for the mortgage credit institutions. The mortgage credit institutions exclusively offer loans secured by mortgages on real estate within certain statutory limits, so risk weights are lower.

| Risk weights for Icelandic, Faroese and Danish SIFIs | Chart 3 |

|---|

|

Note: The average risk weight is calculated as the ratio between the institution's total risk-weighted exposures and the total assets of the institution for Q2 2019. Data for Iceland are for end-2018.

Source: Financial statements and own calculations. |

Risk weights by segments

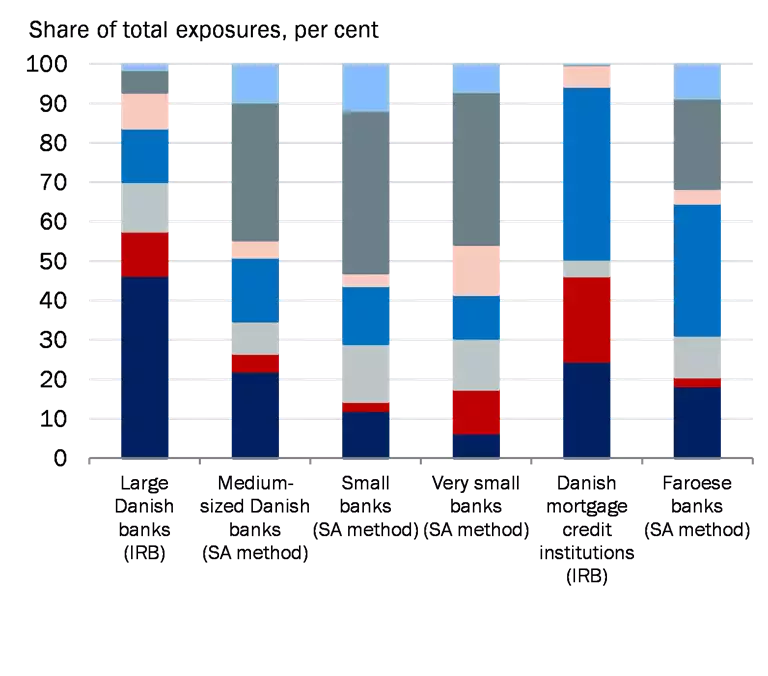

Faroese banks have a high share of exposures secured by mortgages on real estate. The risk weight for these exposures is relatively low, which helps to explain why the total average risk weight of the Faroese banks is slightly lower than that of the medium-sized Danish banks (group 2), cf. Chart 4.

The total average risk weights in Chart 3 must be seen in the light of the risk weights of the individual segments and the size of the associated exposures. The breakdown into segments in Chart 4 can only be done for credit exposures, while all exposures are included in the total average risk weight.[20]

The large Danish banks have a larger share of loans to corporates than the Faroese banks and other Danish banks. The IRB risk weights for corporate exposures are significantly lower than the SA risk weights. The risk weights calculated using the IRB approach depend, inter alia, on the individual circumstances of customers and the institution's loss history and may therefore vary over time.[21]

| Exposures and risk weights by segments (SA and IRB) | Chart 4 |

|---|

| Breakdown of exposures, Q3 2019 |

Average risk weights by segments, Q3 2019 |

|

|

|

Note: The risk weights are the institutions' average risk weights for the specified credit exposure segments measured according to the SA and IRB methodologies. The average risk weight is calculated as the ratio between the institution's risk-weighted exposures to the segment in question and the institutions' total exposures to the segment. For the IRB institutions, some exposures to 'Corporate sector' may be secured by mortgages on real estate. Some of the large Danish banks' portfolios are calculated according to the SA method. 'Public etc.' includes public corporations. 'Other' includes non-performing exposures, exposures that carry a particularly high risk etc.

Source: The Danish FSA. |

Impairment charges and losses in Faroese and Danish banks

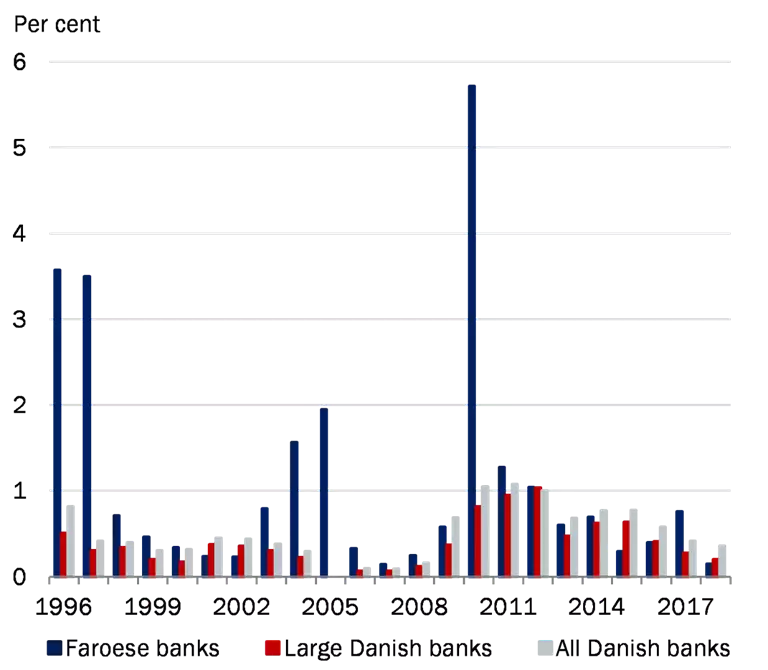

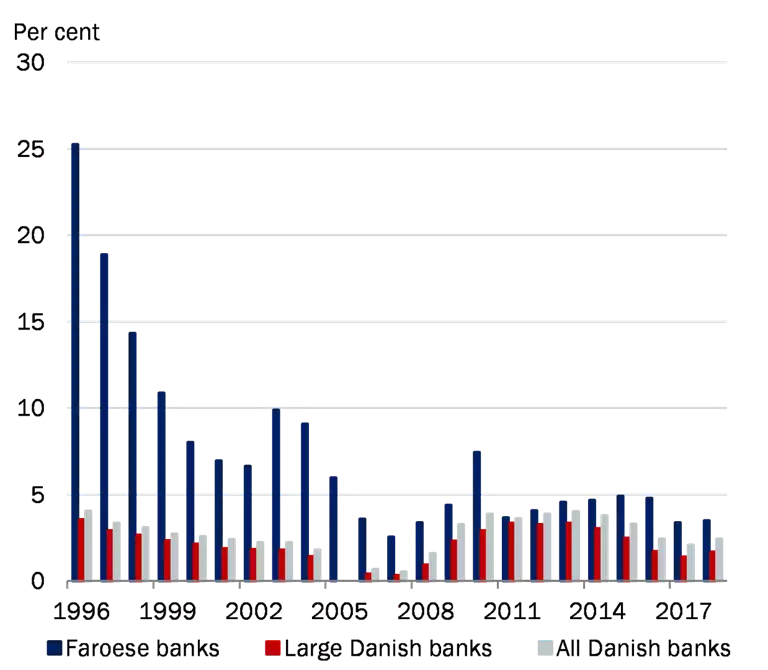

As mentioned before, the IRB risk weights are typically lower than the weights calculated using the SA method. This should be seen in light of the fact that institutions with IRB authorisation are often large and have a highly diversified portfolio with a loss history justifying the approval of low risk weights. Since 1996, the Faroese banks have posted higher losses and impairment charges than the Danish SIFIs with IRB authorisation, cf. Chart 5. This is an indication that, if given IRB permission, the Faroese banks' risk weights would not be as low as those of the Danish SIFIs. It is especially on corporate loans that the Faroese banks post higher losses and impairment charges than the Danish SIFIs, cf. Appendix C.

| Banks' losses and impairment charges | Chart 5 |

|---|

| Losses |

Impairments charges |

|

|

Note: The banks' accumulated losses and accumulated impairment charges in per cent of lending before impairment charges.

Source: The Danish FSA. |

4. Capital requirements and lending

Credit institutions fund their lending with a mix of equity and debt. The capital requirements introduce minimum criteria for the share of equity funding. It is therefore a common assumption that binding capital requirements reduce lending and increase lending rates. The argument is that equity is an expensive source of funding compared to debt due to the higher required return on equity because any losses on assets are first absorbed by equity.

The argument that equity is expensive overlooks the fact that an increase in equity makes the credit institution more resilient to losses on assets. With higher equity, the bank will be able to absorb correspondingly higher losses on its assets before creditors are affected. This reduces the risk of creditors suffering losses. For both creditors and shareholders, the risk is thus lower, the more equity the bank has. The lower risk is normally reflected in lower interest rates on a bank's debt and a lower required rate of return on equity. Empirical evidence supports markets meeting well-capitalised institutions with a lower required rate of return.[22]

A bank may adjust to higher capital requirements in different ways, cf. Box 1. Experience with the transition to Basel III in Denmark does not suggest that higher capital requirements has reduced lending.[23]

| Possible ways of adjusting to higher capital requirements | Box 1 |

|---|

|

The effects of higher capital requirements will depend on the institutions' ability to adjust. Generally speaking, the institutions can:

- increase their capital by retaining earnings rather than paying dividends and/or raising capital in the market;

- reduce their risk-weighted assets, which can be done by reducing lending and/or changing their asset mix towards lower risk weight sectors;

- reduce their excess capital adequacy, i.e. their voluntary buffer over and above the capital requirement.1

In practice, the effects of the institutions' adjustment will depend on the financial and economic situation.2 The adjustment also includes a temporal perspective, e.g. it will probably take longer to increase capitalisation through higher earnings than by raising new capital. Changing the asset mix is also likely to take a long time.

|

1: However, there may be a market requirement for a certain level of capital or excess capital adequacy.

2: Cf., for example, Harimohan (2014), How might macroprudential capital policy affect credit conditions?, Bank of England, Quarterly Bulletin, Q3. |

Excess capital adequacy in Faroese banks

There have been no signs of a decline in lending in the Faroe Islands in recent years, despite an increase in buffer requirements. At the same time, there has been an economic upswing in the Faroe Islands.

All banks will be able to meet the phased-in buffer requirements and the systemic risk buffer of 3 per cent from 1 January 2020. Table 4 shows an overview of the capital buffer requirements and excess capital adequacy of the four Faroese banks.[24]

The Faroese banks' primary funding sources are deposits and equity. Since a share of 45 per cent of bank deposits is not covered by the deposit guarantee, cf. Appendix A, it would therefore be expected to be sensitive to risks in the banks.

| Capital requirements and excess capital adequacy, Q2 2019 | Table 4 |

|---|

| Per cent of risk exposures |

BankNordik |

Betri Banki |

Norðoya Sparikassi |

Suðuroyar Sparikassi |

Minimum requirements (Pillar I)

Minimum common equity capital (CET1) requirement

Capital add-on (Pillar II)

Total buffer requirement 20201

Total capital requirement

- Common equity capital (CET 1) requirement

Total solvency ratio

- Common equity capital ratio (CET 1)

Excess capital adequacy2

- Excess CET 1 adequacy |

8.0

4.5

1.5

7.0

16.4

14.3

19.6

17.5

3.2

3.2 |

8.0

4.5

2.5

7.5

17.9

17.9

25.9

25.9

8.0

8.0 |

8.0

4.5

2.7

7.0

17.6

15.8

20.4

18.5

2.7

2.7 |

8.0

4.5

1.6

5.4

15.0

13.4

16.1

14.5

1.1

1.1 |

1: The 2 per cent countercyclical capital buffer in Denmark (from December 2020) is included in the total buffer requirement, which is primarily of importance for BankNordik. The systemic risk buffer in Faroe Islands applies only to domestic exposures and will be 3 per cent on 1 January 2020.

2: The excess capital adequacy has been calculated on the assumption of unchanged capital ratios and Pillar II add-ons. Some of the institution-specific solvency requirement can be fulfilled by types of capital other than common equity capital.

Source: The Danish FSA. |

5. SIFI requirements

A SIFI experiencing difficulties could lead to negative repercussions for the economy. SIFIs are therefore subject to additional requirements to reduce the probability of the institutions failing and limit the negative consequences in case of their failure.

Once an institution is designated as a SIFI, it must comply with a number of additional requirements compared to non-SIFIs. SIFIs must comply with a SIFI capital buffer requirement and a higher MREL requirement, cf. below. In addition, SIFIs are subject to more intensified ongoing supervision, cf. Box 2.

| Additional requirements for SIFIs 1 | Box 2 |

|---|

| In addition to the SIFI buffer and specific MREL requirements with a resolution plan, Faroese SIFIs are subject to more intensified ongoing supervision. This includes, inter alia, a quarterly conference call with the Executive Board of the SIFI, where minutes from the board meetings of the last quarter and relevant committee meetings are discussed. In addition, SIFIs must annually submit the compliance and risk function's reporting to the Board of Directors and the self-evaluation of the Board of Directors. The material is reviewed at an annual meeting between the supervisory authority and the Executive Board, compliance and risk managers, the chairman of the Board of Directors, the external auditors and any internal audit function. ICAAP and ILAAP reports2, credit and liquidity policies and a small selection of exposures are also discussed with the institution at the meeting.

In general, the Danish FSA applies a principle of proportionality to the Faroese SIFIs compared to the Danish SIFIs. On the other hand, the FSA has greater expectations concerning risk management, the control environment and defence lines of a Faroese SIFI relative to a Danish group 3 institution of comparable size.

In addition, there are higher regulatory requirements regarding the management of a SIFI and its organisation. They include, for example, a requirement to set up remuneration, nomination and risk committees for unlisted companies. In addition, there are limitations on the number of management positions that a board member of a SIFI may assume. |

1: Since the box describes selected requirements, it is not exhaustive.

2: ICAAP (Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process) and ILAAP (Internal Liquidity Adequacy Assessment Process) are the institutions' internal processes for assessment and management of capital and liquidity conditions. Institutions are required to have these processes and draw up annual reports to the supervisory authorities.

Source: The Danish FSA. |

SIFI buffer

The purpose of the SIFI buffer is to reduce the probability that a SIFI will fail. The SIFI buffer requirements in Denmark and in the Faroe Islands depend on the systemic importance of each institution.[25] The systemic importance of Faroese SIFIs is calculated as half the average of three indicators:

- Balance sheet as a percentage of the aggregate balance sheet of Faroese banks

- Lending in the Faroe Islands as a percentage of banks' total lending in the Faroe Islands

- Deposits in the Faroe Islands as a percentage of banks' total deposits in the Faroe Islands

The two most systemic banks in the Faroe Islands are subject to a 2 per cent SIFI requirement, while the requirement for Norðoya is 1.5 per cent, cf. Table 5. The three Icelandic SIFIs are all subject to an additional 2 per cent SIFI buffer requirement regardless of their degree of systemic importance.

| SIFI-bufferkrav for 2019 for færøske og danske SIFI'er | Table 5 |

|---|

| |

Systemic importance |

Faroese SIFIs |

Danish SIFIs |

SIFI buffer |

| Category 1 |

≤5 |

- |

DLR Kredit A/S (1.9)

Spar Nord Bank A/S (2.0)

Sydbank A/S (3.1) |

1.0 per cent |

| Category 2 |

[5-15[ |

Norðoya Sparikassi (5.7) |

Nordea Kredit Realkredit A/S (5.2)

Jyske Banks A/S (9.3) |

1.5 per cent |

| Category 3 |

[15-25[ |

Betri Banki P/F (19.2)

P/F BankNordik (23.4) |

Nykredit Realkredit A/S (18.9) |

2.0 per cent |

| Category 4 |

[25-35[ |

- |

- |

2.5 per cent |

| Category 5 |

≥35 |

- |

Danske Bank A/S (36.1) |

3.0 per cent |

Note: The figures in brackets indicate the systemic importance of the institution, calculated and published by the Danish FSA in connection with the SIFI designation for 2019. The systemic importance is for the Faroese and Danish sectors, respectively.

Source: Ministry of Industry, busniess and Financial Affairs and the Danish FSA. |

In Denmark and the Faroe Islands, the SIFI buffer is implemented via the systemic risk buffer. Further specification in the new EU Capital Requirements Directive, CRD V, means that in future, SIFI requirements must be implemented through the so-called O-SII buffer[26], intended for national SIFI requirements.

MREL requirements

As part of the resolution planning, the Danish FSA sets a minimum requirement for eligible liabilities (MREL) for each institution or group, including the Faroese institutions. The MREL requirement aims to ensure sufficient liabilities for loss absorption in the institution in a resolution situation and for any recapitalisation of the institution in accordance with the chosen resolution strategy. Consequently, the MREL is to contribute to ensuring a resolution process without the use of government funds, and without such resolution having any substantial negative impact on financial stability.

In June 2018, the Danish FSA published preliminary MREL principles for Faroese banks, where the MREL requirements are to be phased in from 2020 to 2025.[27] The MREL requirements for Suðuroyar Sparikassi and BankNordik were set in 2019, while the requirements for Betri Banki and Norðoya Sparikassi have not yet been set.

MREL requirements can be met using non-preferred senior debt or other loss-absorbing liabilities and own funds, such as equity. Hence, institutions can meet MREL requirements by withholding earnings or issuing new capital and debt instruments. Accordingly, if the Faroese banks cannot meet the MREL requirement using equity, they must issue MREL instruments. The implications may be that banks increase their balance sheets and that they are exposed to refinancing risks in international capital markets, where they currently (as mentioned above) rely on equity and deposits as their primary funding sources. Like banks, savings banks can issue non-preferred senior debt.

The experience from Denmark is that even small institutions, including savings banks, have been able to issue non-preferred senior debt to meet their MREL requirements. However, this goes for a limited number of institutions whose issuances have been modest in size. In the opinion of the Danish FSA, solid earnings and solvency are prerequisites for issuance. The current low interest rate environment, where investors are looking for returns, also plays an important role.

Small banks normally issue non-preferred senior debt to one or a few investors in a closed process in cooperation with an investment bank.

Since Iceland has not implemented the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive, BRRD, it has not set MREL requirements yet.

Resolution

If a non-SIFI is failing, the initial response would be to seek a market solution. This means that private solutions will be sought, including merger with a stronger institution. If this is not possible, an orderly wind-down must be carried out, divesting assets to the greatest possible extent, while the remainder is transferred to the resolution authority Finansiel Stabilitet for resolution. Cf. Box 3 on resolution of non-SIFIs in Denmark.

| Resolution of non-SIFIs in Denmark | Box 3 |

|---|

| Finansiel Stabilitet draws up draft resolution plans for non-SIFIs and submits them to the Danish FSA, which, in its capacity as resolution authority, adopts the resolution plans and after consulting Finansiel Stabilitet, sets MREL requirements.

As a general rule, Finansiel Stabilitet finds that it is in the public interest to resolve all non-SIFIs without the use of bankruptcy. The assessment is that it is in the public interest that all depositors have access to their accounts on Monday morning after a resolution weekend, so even the smallest non-SIFIs will be resolved without resorting to bankruptcy. The preferred resolution strategy thus involves (partial) restructuring of the institution in order to continue the viable parts through a sales process, while any remaining non-marketable activities are resolved under the control of Finansiel Stabilitet. The strategy implies that losses are borne by the institution's owners and creditors through the write-down of liabilities as necessary. The MREL requirement for non-SIFIs will be higher than in the case of bankruptcy and lower than for restructuring (which is the resolution strategy used for SIFIs).

The model for setting MREL requirements for non-SIFIs will need to be reassessed under the new Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive, BRRD II. However, the MREL requirement is expected to be at the same level as today |

| Source: The Danish FSA |

6. Systemic risk buffer and countercyclical capital buffer

National authorities must decide the levels of the countercyclical capital buffer and the general systemic risk buffer.[28] Currently, the countercyclical capital buffer is 0 per cent in the Faroe Islands, while the general systemic risk buffer is 3 per cent as from 1 January 2020.

6.1 Systemic risk buffer

The general systemic risk buffer is intended to make Faroese banks more resilient to structural risks in the Faroe Islands.[29] The structural risks are a consequence of the fact that the Faroe Islands is a small, open economy with a concentrated business structure. This makes the economy vulnerable to negative shocks which may, via direct and indirect effects, entail losses in the banking sector and amplify real economic fluctuations. Historically, the Faroese economy has experienced large fluctuations and considerable variation in the loan impairment charges of Faroese banks.

The systemic risk buffer is of a permanent nature and cannot be released, contrary to the countercyclical capital buffer. The Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs assesses the general systemic risk buffer and the SIFI buffer once a year.

Implementation of the systemic risk buffer

The general systemic risk buffer applies to exposures in the Faroe Islands and to all Faroese banks. For SIFIs, the general systemic risk buffer rate is an add-on to the SIFI requirements. This will continue to be the case following the implementation of the SIFI requirements via the O-SII buffer, i.e. when the new EU Capital Requirements Directive is implemented in Danish and Faroese legislation. As the systemic risk buffer and O-SII buffer address different risks, they can be added.

Danish banks with exposures in the Faroe Islands must also meet the general systemic risk buffer requirement.[30] For other countries, recognition (reciprocity) of actions via the systemic risk buffer is voluntary.

6.2 Countercyclical capital buffer

The aim of the countercyclical capital buffer is to contribute to limiting the negative effects on the real economy of a future financial crisis. The buffer is to be released if stress occurs in the financial sector and there is a risk that banks will tighten credit to households and corporates so much that a credit squeeze may arise. The buffer does not necessarily have to be released in an economic slowdown.

The purpose of the countercyclical capital buffer is to make institutions more resilient. The aim is not to curb house price increases or high lending growth in good times.

The buffer must be built up when systemic financial risks increase and before financial imbalances grow too large. Due to the complexity of measuring and identifying systemic risks and financial imbalances, the Systemic Risk Council uses a broad information basis to assess financial system developments in Denmark.[31] The buffer rate is not set mechanically on the basis of individual indicators, given the uncertainty associated with measuring the evolution of systemic risks.

For the Faroe Islands, a broad information basis is also used, although there are less financial indicators for the Faroe Islands than for Denmark. The assessment of the level of the countercyclical capital buffer rate must also take account of other relevant information, including other policy actions. The general systemic risk buffer increases the banks' resilience to large fluctuations in the Faroese economy. The cyclical fluctuations to be addressed by the countercyclical capital buffer must therefore be pronounced before the buffer is activated. This is not considered to be the case at this stage.

Process of changing the countercyclical capital buffer

If the Systemic Risk Council in Denmark finds that the countercyclical capital buffer needs to be changed, the Council will publish a recommendation addressed to the Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs. When discussing Faroese matters, representatives of the Faroese Risk Council are invited to participate. The Minister is responsible for setting the buffer rate on a quarterly basis. It generally takes 12 months from the Minister's announcement of an increase in the buffer rate until the institutions must meet the requirement.

Any change to the buffer rate for the Faroe Islands will be delayed by one quarter relative to the setting of the Danish buffer rate. The reason is that the Faroese authorities must be consulted before any change to the countercyclical capital buffer rate, including the first time it is set at a level greater than zero.

A positive countercyclical capital buffer in the Faroe Islands must also be met by credit institutions in EU member states with credit exposures in the Faroe Islands.[32]Each institution is subject to an institution-specific countercyclical capital buffer. It is calculated as the weighted average of the buffer rates applicable in the countries where the institution has credit exposures. The weighted buffer rate is then multiplied by the institution's total risk-weighted exposures.

Systemic risk buffer and countercyclical capital buffer in other countries

The systemic risk buffer has been implemented in several other European countries at levels depending on their respective structural vulnerabilities. In some countries, the buffer is used as a SIFI buffer, while in other countries it is used as a general buffer to address structural risks for all banks in that country, see Appendix D.

The countercyclical capital buffer is also used in several European countries, including in Denmark, cf. Appendix D. Each country has its own method of assessing the buffer rate and the level set depends on the financial development in that country.

[1] Data have not been updated since the Council's discussions.

[2] In these areas, Danish legislation applies with such deviations as may be dictated by conditions in the Faroe Islands. See also the National Ombudsman in the Faroe Islands, Report 2019.

[3] See Section 23(8) of the Parliamentary Act on the Governmental Bank of the Faroe Islands and the Faroese risk council (Lagtingslov om Færøernes Landsbank (Landsbanki Føroya) og Færøernes Systemiske Risikoråd (Føroya Váðaráð)).

[4] Cf. guidelines on the handling by ministries of matters relating to the Faroe Islands (Vejledning om ministeriers behandling af sager vedrørende Færøerne) (in Danish), item 3.1.

[5] See a description of the methods in section 3 about capital buffer requirements and risk weights.

[6] Danish experience from the transition to Basel III does not suggest that increased capital requirements will result in a fall in lending, cf. Danmarks Nationalbank, Capital requirements for banks – myths and facts, Danmarks Nationalbank Analysis, No. 8, June 2018.

[7] At the end of 2018, the threshold for the deposits indicator was reduced to 3 per cent in Denmark, while it remains 10 per cent for the Faroe Islands. The limit value for the balance sheet-to-GDP ratio is 13 per cent for the Faroe Islands (6.5 per cent in Denmark), while the lending indicator is 10 per cent (5 per cent in Denmark).

[8] MREL stands for Minimum Requirement for Eligible Liabilities. These are liabilities eligible for absorbing losses and recapitalising the bank in a resolution situation.

[9] This means that the systemic risk buffer will not be included in the recapitalisation amount. The Danish FSA decided BankNordik's MREL requirement at the end of November (26 November 2019).

[10] The countercyclical capital buffer is also included only once.

[11] Based on data for September 2019.

[12] Iceland is part of the European Economic Area (EEA), but is not a member of the EU.

[13] The thresholds were set at a time when the Danish banking sector accounted for approximately 400 per cent of Denmark's GDP, while the Faroese banking sector represented 200 per cent of the Faroese GDP. Today, the factor is still about 2. The Danish banking sector (measured on balance sheet) accounted for 358 per cent of Denmark's GDP in 2018, while the Faroese banking sector accounted for 154 per cent.

[14] Cf. EBA/GL/2014/10.

[15] According to Spar Nord's 2018 risk report, a project has been launched to enable it to transition from the SA method to the IRB method over a period of three to four years.

[16] Two of the key parameters are PD and LGD: Probability of Default (PD) is the probability of a loan defaulting in the coming year. Loss Given Default (LGD) is the expected loss ratio given default on the loan.

[17] There are cases where the IRB method results in higher risk weights than the SA method, e.g. for Ireland, cf. Döme and Kerbl, Comparability of Basel risk weights in the EU banking sector, Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2017. One explanation may be that Ireland was hit hard during the 2007-08 financial crisis. As historical losses are included in the calculation of IRB risk weights, the heavy losses suffered by Irish banks during the financial crisis will be reflected in higher risk weights when using the IRB approach.

[18] Another upcoming requirement (described in Appendix B) is a minimum requirement for the leverage ratio of institutions. Based on current exposures, this will not be the binding minimum requirement for Faroese banks as the risk-based minimum requirement is higher. However, it will be the binding minimum requirement for a number of Danish SIFIs.

[19] The positioning of the Faroese banks in relation to all the Danish institutions is shown in Chart C1 of Annex C.

[20] The total average risk weight in Chart 3 also includes risk-weighted exposures attributable to counterparty risk, market risk and operational risk. However, the vast majority of exposures are attributed to credit risk.

[21] The development in Danish SIFIs' risk weights up to 2015 is described in Chapter 4: Capital requirements and risk weights, Financial Stability, 1st half 2016, Danmarks Nationalbank.

[22] Cf. Danmarks Nationalbank, Capital requirements for banks – myths and facts, Danmarks Nationalbank Analysis, No. 8, June 2018.

[23] Cf. Danmarks Nationalbank, Capital requirements for banks – myths and facts, Danmarks Nationalbank Analysis, No. 8, June 2018.

[24] In Q3 2019, BankNordik issued Additional Tier 1 capital, which is not included in the table with Q2 data.

[25] Like the SIFI designation, the SIFI requirements under Danish, and subsequently Faroese, legislation are based on the October 2013 political agreement (Bank Rescue Package 6).

[26] "Other Systemically Important Institutions" buffer.

[27] It is clear from the preliminary principles and the recent decision on MREL for BankNordik that the general systemic risk buffer for exposures in the Faroe Islands and the countercyclical capital buffer will not be included in the MREL recapitalisation amount. These buffers will thus be included in the MREL for SIFIs only once.

[28] Another buffer requirement that all banks must meet is the capital conservation buffer requirement. It helps to ensure that individual banks remain solvent during periods of unexpected losses. The buffer level is 2.5 per cent in all EU member states. It is possible to increase the buffer temporarily if the development of systemic risks so requires.

[29] Cf. also the Council's recommendations on the systemic risk buffer on its website, www.risikoraad.dk.

[30] This applies to banks with exposures in the Faroe Islands exceeding kr. 200 million, cf. the Ministry of Industry, Business and Financial Affairs' announcement on increasing the systemic risk buffer for exposures in the Faroe Islands, 25 June 2018 (in Danish).

[31] Cf. also the Council's method paper 'The countercyclical capital buffer' on the Council's website, www.risikoraad.dk.

[32] Reciprocity is mandatory up to a limit of 2.5 per cent, cf. Article 139(3), second paragraph, in CRD IV.