The war in Ukraine has resulted in increased uncertainty about the future development of the economy and financial conditions. The Council is ready to recommend a reduction of the buffer rate with immediate effect if stress occurs in the financial system and there is a risk of severe tightening of credit granting to households and companies.

The buffer needs to be built up early so that capital can be released in the event of stress in the financial sector

The buffer should be built up before financial imbalances become excessive and the financial sector becomes vulnerable to negative shocks. When the buffer is increased, additional capital will be built up. This capital can be released when a need arises at some point in the future. Therefore, the Council's position is that the buffer must be built up quickly and gradually to 2.5 per cent.

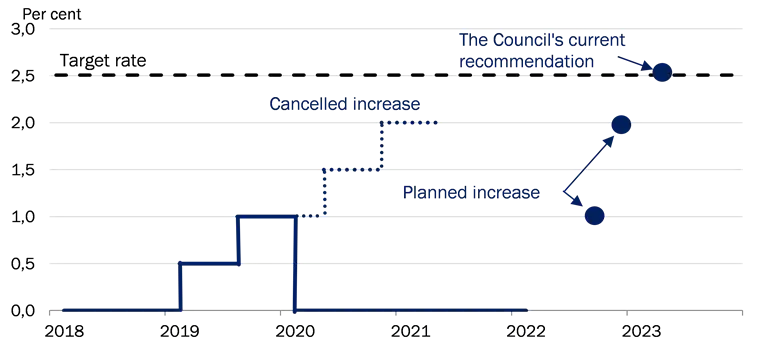

In December 2021, the Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs chose to comply with the Council's recommendation to increase the countercyclical capital buffer. A buffer rate of 2.0 per cent will therefore apply from 31 December 2022. If the Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs complies with the present recommendation, the credit institutions will have to comply with a buffer rate of 2.5 per cent from the end of March 2023, see chart 1.

| The Council wants the countercyclical capital buffer to be increased |

Chart 1 |

|

|

Note: The buffer rate shown is the current rate to be complied with by the credit institutions. The dot in the 1st quarter of 2023 shows when the credit institutions must comply with a buffer rate of 2.5 per cent if the Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs complies with the Council's recommendation.

Source: Danmarks Nationalbank

|

Every quarter, the Council assesses what is a suitable countercyclical capital buffer level. If the Council finds that the rate should be changed, it will publish a recommendation addressed to the Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs. The Minister is required, within a period of three months, to either comply with the recommendation or present a statement explaining why the recommendation will not be complied with.

The Council sets the buffer rate based on an overall assessment of the development in the financial system.[1] In addition to a number of indicators of financial system development, the Council also includes other relevant information, such as other policy measures, as well as current and future requirements to be met by the institutions.

The Council's website contains a number of frequently asked questions and answers with more information on how the countercyclical capital buffer is set in Denmark.[2]

The Council is ready to recommend a reduction of the buffer rate with immediate effect if stress occurs in the financial system and there is a risk of severe tightening of credit granting to households and companies.

Risk build-up in the financial system

The Council finds that risks are currently being built up in the financial system. High risk appetite, low interest rates, accommodative financing terms and high economic growth create a fertile ground for build-up of risks. Despite increased uncertainty about the future economic development and financial conditions, this is a good time to build up the countercyclical capital buffer.

There are signs of high risk appetite and risk-taking in Danish households and in the financial markets. Danish households bought foreign equities and investment fund shares for historically large sums in 2020 and 2021. The war in Ukraine has caused increasing volatility and price decreases early 2022, but equity prices remain at a high level following sharp price increases in 2021. House prices also rose significantly in 2021.

The central banks' monetary policy remains accommodative. However, the central banks have begun to react to the high inflation figures. The Fed began scaling down its bond purchase programme in November 2021 and raised interest rates in March 2022. The Fed expects to make several interest rate hikes in 2022. The ECB is also scaling down its asset purchase programmes and is not ruling out interest rate increases in 2022. The market participants expect the Fed to make significant interest rate hikes in 2022. The markets also expect the ECB to raise interest rates in 2022, although on a smaller scale than the Fed. However, the central banks' signals and the market's expectations still indicate an accommodative monetary policy and low interest rates, albeit now at a higher level, for an extended period to come.

During covid-19, the institutions' credit granting has been subdued as a consequence of the government relief packages to the corporate sector. Credit growth is currently moderate, but increasing, one reason being the phasing out of the relief packages and high housing market activity. However, despite the overall moderate credit growth, some segments are experiencing high credit growth. Lending to households has risen in step with increasing housing market activity. Lending growth is particularly high in areas with high increases in house prices. The proportion of loans with deferred amortisation has been increasing since 2020. In addition, there has been increasing growth in corporate credit granting, one reason being that deferred tax and VAT payments are beginning to fall due. Even if total credit growth remains moderate, the risks are exacerbated by lending already being at a high level.

As a consequence of the government relief packages, central government debt has risen sharply in both the United States and Europe. This reduces the likelihood of states being able to mitigate the negative effects of a future crisis. Likewise, central banks' leeway is limited by continued low interest rates and historically high balances. This highlights the importance of the credit institutions being resilient and having the necessary capital to support their lending in a future crisis situation.

Both the Danish and international economies are seeing continued growth, but the war in Ukraine will dampen this momentum. Denmark has been largely free of covid-19 restrictions since February. Strong domestic demand at the end of 2021 has continued into 2022 and has not been significantly affected by restrictions around the New Year. The same applies to demand from abroad, where the economic consequences of the waves of infection during winter have also been milder than in previous waves of infection. Strong demand has meant a heavy increase in employment, and unemployment has fallen significantly. Strong demand and fierce competition for labour are expected to result in higher pay increases in the coming years. However, the war in Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia will put a damper on economic growth both in Denmark and internationally. The extent and duration of the economic consequences of the war are connected with great uncertainty and will depend greatly on how the war develops and on the political reactions.

Price increases are continuing at a high pace. The high inflation figures are especially caused by energy price increases. Energy and commodity prices have been pushed up further by the war in Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia, which could contribute to keeping inflation figures high in the coming period. At the same time, higher pay increases could mean that the underlying inflation will be higher over the next years than in the years leading up to the pandemic. Companies' costs have also increased, including as a result of continued supply chain bottlenecks and energy price increases, which have also begun to rub off on consumer prices.

The above assessment forms the basis of the Council's recommendation that the Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs increase the countercyclical capital buffer. The Council also notes that both Sweden and Norway are in the process of building up the buffer again.

The indicators in the Council's information set have been elaborated on in Appendix A. There is no mechanical correlation between the indicators and the buffer rate, given the uncertainty of measuring the development in systemic risks, including that historical indicators are not necessarily adequate markers of the future development. The Council's buffer rate assessment is therefore based on an overall assessment of the indicators in a more long-term perspective as well as other relevant information, such as the interaction with other requirements.

The institutions have the capital required to meet a countercyclical capital buffer requirement of 2.5 per cent

As at 31 December 2021, Danish credit institutions had enough capital to meet a requirement for a countercyclical capital buffer of 2.5 per cent.[3] This applies both to the institutions' capital adequacy requirement and their MREL requirement, see the section Other capital adequacy requirements.

The higher countercyclical capital buffer requirement will enter into force 12 months after the Minister has announced an increase, which means that the requirement will have to be complied with from the end of March 2023 at the earliest. The institutions thus have time to adjust.

A buffer rate increase from 2.0 to 2.5 per cent raises the total regulatory requirement for Danish institutions' equity by approximately kr. 7,5 billion. By comparison, the total earnings of the sector were approximately kr. 37.5 billion after tax in 2021. The excess capital adequacy was approximately kr. 150 billion at the end of 2021[4].

The requirement that the institutions maintain a countercyclical capital buffer is not a hard requirement. This means that the institutions will not lose their banking licence if they fail to meet the requirement. Instead, the institutions will be required to submit a capital conservation plan to the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority, and bonus and dividend payments etc. will also be restricted if they fail to meet the total capital buffer requirement.[5]

The purpose of the buffer is to increase the institutions' resilience and ensure credit granting during periods of financial stress

The countercyclical capital buffer is an instrument used to make the institutions more resilient by increasing the requirement for their capitalisation during periods in which risks build up in the financial system. If financial stress occurs with a risk of a severe tightening of credit granting, the buffer can be reduced with immediate effect, thus releasing capital to the institutions.

To the extent that the institutions do not use the released capital to absorb losses, they may use it for new lending or to secure their excess capital adequacy. This improves the possibility for credit institutions to maintain an adequate level of credit granting during periods of stress in the financial system. The buffer thus contributes to limiting negative effects on the real economy in the event of financial stress.

The Council's strategy is that the buffer should be introduced gradually. This makes it easier for the institutions to adapt to the new, higher capital requirements, for example by retaining earnings. The institutions will also be able to adapt more easily to higher buffer requirements in periods like the current one when the economy is doing well and the institutions have low losses. The Council therefore expects that any negative effect on the institutions' credit granting in Denmark will be limited.[6] The Council also assesses that the Danish institutions will not significantly change their credit granting abroad as a result of an increase in the countercyclical capital buffer in Denmark. The Council's assessment is based on a number of factors, including the fact that the largest foreign exposures are primarily in Sweden and Norway. The buffer is also being built up in both these countries, see appendix B.

The buffer is first and foremost an instrument for making the credit institutions more resilient. It cannot be used as an instrument to control financial cycles, neither in an upswing nor in a downturn. The buffer must be released in situations where there is a risk of a severe tightening of credit granting to households and companies, and therefore not necessarily in connection with a cyclical slowdown.

Other capital adequacy requirements

The Council also takes account of other policy measures in its reflections on the countercyclical capital buffer rate. Account is taken of other current requirements and the phasing-in of future requirements for the institutions.

MREL requirement

The MREL requirement is a minimum requirement for the institutions' eligible liabilities (MREL). The MREL requirement has been fully phased in for the systemic institutions except Spar Nord and Arbejdernes Landsbank. The MREL requirement will be gradually phased in for these institutions towards 2024 and 2026, respectively. The MREL requirement concerns eligible liabilities that can absorb losses and recapitalise an institution in connection with resolution. The MREL requirement differs significantly from the countercyclical capital buffer. The purpose of the MREL requirement is to ensure that the institutions can be restructured or wound up without the use of government funds, and without such resolution having any substantial negative impact on financial stability. The MREL requirement consists of a risk-based requirement and a non-risk-based requirement, with the highest of the two requirements being binding. For the systemic institutions, the risk-based MREL requirement consists of a loss absorption amount corresponding to the institution's solvency requirement (the minimum requirement) and a recapitalisation amount corresponding to the institution's solvency requirement plus a market confidence buffer. The market confidence buffer is calculated as the institution's combined buffer requirement less the countercyclical capital buffer. The non-risk-based MREL requirement consists of twice the leverage ratio requirement.

The MREL requirement can be met with several types of capital and debt instruments. The institutions must have sufficient capital and debt instruments to comply with the MREL requirement, and they must also have separate capital to comply with the combined buffer requirement, including the countercyclical capital buffer. Therefore, capital used to meet the combined capital buffer requirement, including the countercyclical capital buffer requirement, cannot concurrently be used to meet the MREL requirement. The combined capital buffer requirement can only be met with Common Equity Tier 1 capital.

The Danish Financial Supervisory Authority's overall assessment is that the phasing in of the non-systemic banks' individual MREL requirements towards 2024 will not have a major impact on their ability to meet a countercyclical capital buffer of 2.5 per cent. During 2021, several small institutions have issued MREL debt to meet their MREL requirement. The Danish Financial Supervisory Authority expects that the small banks will, to a large extent, be able to meet the future increases in the MREL requirement via their existing MREL funds and through retained earnings. The systemic institutions meet their MREL requirements with their current capital and debt instruments and may, if necessary, increase their excess capital adequacy relative to the MREL requirement by issuing MREL instruments or by retaining earnings.

Minimum requirements for eligible liabilities for groups engaged in mortgage lending

From 2022, groups engaged in mortgage lending must meet a new minimum requirement, as eligible liabilities must represent at least 8 per cent of the groups' liabilities. In practice, this means that if a group's total capital, buffer and MREL requirements (including debt buffer for mortgage lending activities) constitute less than 8 per cent of its total liabilities, the debt buffer for the mortgage lending activities will increase until the total group requirements represent 8 per cent of the group's liabilities. Some groups engaged in mortgage lending will therefore experience an increase in their MREL requirement. Groups engaged in mortgage lending to a large extent use capital to meet their MREL requirement and debt buffer requirement, but they have an opportunity to issue additional non-preferred senior debt in their efforts to comply with the MREL requirement.

Leverage ratio

Since July 2021, the institutions have been subject to a minimum leverage ratio requirement. While the buffer is calculated in relation to risk-weighted exposures, the leverage ratio is calculated in relation to non-risk-weighted exposures. For groups with a large share of assets with very low risk weight, such as mortgage loans, the leverage ratio requirement entails a higher capital requirement than the risk-based capital requirement. The leverage ratio requirement and the risk-based capital requirement are two parallel capital requirements that are independent of each other. Therefore, an increase of the countercyclical capital buffer does not affect the leverage ratio requirement.

Output floor

The Basel Committee's output floor is scheduled to be implemented gradually in the EU from 2025 to 2029. According to the Basel Committee, the purpose is to ensure a more uniform calculation of risk-weighted exposures across countries. The output floor requirement limits how low the risk weights can be in the institutions' risk assessment of exposures when they use internal models to calculate the capital requirement. For institutions using internal models, this may result in an increase of their risk-weighted exposures and thus also an increase of their risk-based capital requirements. The output floor will be of a permanent nature, whereas the countercyclical capital buffer requirement can be reduced when risks materialise. The output floor must first be adopted by the EU before being introduced for the Danish institutions.

The European Commission proposed the implementation of the output floor in October 2021. In addition to the recommendations of the Basel Committee, the proposal envisages a transitional period with favourable weighting of housing lending within a loan-to-value ratio of 80 per cent. The transitional schemes are planned to be phased out and discontinued at the end of 2032, which means that the output floor will only have full effect from 2033. The Commission's proposal also contains provisions on the compliance with the other risk-based requirements in case of a binding output floor. Here, the authorities must reassess and potentially adjust the size of both the institutions' individual capital adequacy requirements under Pillar II, and the systemic risk buffer rate and the SIFI buffer rate, if these are applicable. This must be done to avoid that the institutions' total capital adequacy requirements become too high in relation to the underlying risk. However, there is no requirement for a reassessment of the countercyclical buffer rate.

The Council's recommendation is in compliance with current legislation.

Lars Rohde, Chairman of the Systemic Risk Council

Statements from the representatives of the ministries on the Council

"Legislation regarding the Systemic Risk Council stipulates that recommendations addressed to the government must include a statement from the representatives of the ministries on the Council. Neither the representatives of the ministries nor the Danish Financial Supervisory Authority have the right to vote on recommendations addressed to the government.

The government notes the Council's recommendation to the government to set the rate of the countercyclical capital buffer at 2.5 per cent with effect from 31 March 2023. The Minister for Industry, Business and Financial Affairs will announce the government's decision on the rate of the countercyclical capital buffer for the 1st quarter of 2022 as soon as possible."

Appendix A – Indicators

The Council includes a number of selected key indicators in its assessment of the buffer rate to capture the build-up of systemic risk at various stages in the financial development. Supplementary indicators and other relevant information are also taken into account in the assessment to provide a more detailed picture than that shown by the key indicators.

The early stage of an economic upswing is often characterised by increasing risk appetite among investors.[7] This is reflected in higher asset prices, including prices of residential properties and commercial real estate, and eased credit standards for households and companies. At a later stage in the financial development, households and companies may increase their debt in the expectation that property prices will continue to rise. This means that some indicators, such as property prices, signal the build-up of systemic risk ahead of other indicators, for example lending to households and companies.

The indicators included by the Council in the information basis are outlined below. The indicators are divided into relevant categories.[8]

Risk perception

Risk perception in the financial markets has been very low for a number of years, again only temporarily interrupted for a short period in the early stages of the covid-19 pandemic. Equity prices remain high, even though 2022 has begun with rising volatility and price decreases. At the same time, interest rate levels and expected returns on conventional investment products have been very low. To compensate for the low expected returns, several pension companies have undertaken increased risks in the form of more risky investments in alternatives. Likewise, households have undertaken increased risks by increasing the proportion of their wealth that is invested in high-risk equities or investment funds. Danish households bought foreign equities and investment fund shares for a record amount in 2021. Market participants expect a continued accommodative monetary policy in the coming years. Accommodative monetary policy and low interest rates could increase the risk of asset bubbles building up.

Property market

There are signs of risk build-up in the housing market, where a high activity level and large price increases have been seen in 2021. Growth in credit to households remains moderate, but it covers geographical differences, as there are areas in which the credit growth rate has increased significantly. These are especially the areas that have also seen high price growth, such as Copenhagen. At the same time, mortgage loans with deferred amortisation remain very widespread and are again increasing, also among highly indebted homeowners. The very low financing costs in combination with deferred amortisation enable homeowners to incur much debt at a very low debt service. This contributes to increased risk build-up in the housing market in the form of heavy fluctuations in house prices and higher indebtedness.

Credit standards and credit development

Total lending by credit institutions to households and companies is at a high level and has increased moderately since 2015. Growth in corporate lending has generally been greater than to households in recent years and has increased in recent months. Likewise, household credit growth has picked up in connection with the high housing market activity level. Even though the overall credit growth remains moderate, it may mask the build-up of risks, for example if credit quality requirements are eased and if new loans are granted to riskier companies. The credit institutions have very modest direct exposures to Ukraine and Russia.

Every quarter, all EU member states must calculate and publish a so-called 'credit-to-GDP gap' and an accompanying benchmark buffer guide based on the credit-to-GDP gap. The background is that, in retrospective analyses, the credit-to-GDP gap has been a good indicator for predicting systemic bank crises across a number of countries.[9] However, using the credit-to-GDP gap as an indicator of the current credit development poses challenges. One of the weaknesses of the indicator is that it relies on a statistically calculated trend that is boosted by the very high lending growth and the resulting high level of lending in the years leading up to the financial crisis. The credit-to-GDP gap is therefore negative in Denmark.[10] Several other countries had a positive countercyclical capital buffer rate prior to covid-19, even though their credit-to-GDP gap was negative.[11] Due to the challenges associated with using the credit-to-GDP gap as an indicator of the current credit development, the Council includes various credit development indicators in its assessment.

Risk build-up in credit institutions

Favourable developments in the financial sector in recent years – together with large customer funding surpluses in several institutions – have contributed to the build-up of significant capacity among the institutions to increase their lending in general. The customer funding surplus has risen markedly during the covid-19 pandemic as a result of government relief packages and the disbursement of frozen holiday pay. Household loan demand has been increasing since the 2nd half of 2020, and competition for customers has sharpened. Together with optimism and a stronger risk appetite, this could lead to lower credit quality and the easing of credit standards. If credit standards are eased, this could result in losses when the financial cycle reverses.

The institutions have come well through the covid-19 crisis. Most institutions had a return on equity in 2021 which was higher than the pre-pandemic level. The results for 2021 were buoyed by low impairment charges and high customer activity. The institutions have also continued to increase the volume of deposits that are subject to negative interest rates. This may contribute further to rising earnings in the future. If interest rates were to rise in the coming period, this may benefit the institutions' loan margins, and thus their earnings, in the long term. The institutions do not expect their 2022 profits to be just as high as in 2021, but they still expect profits in the vicinity of the levels for the years leading up to the covid-19 pandemic.

Model-based indicators

Estimates of the financial cycle show that the financial development is either on an upward trajectory or at a high level. Analyses of the financial cycle in Denmark show that the cycle is driven primarily by fluctuations in house prices and lending and that house prices have a tendency to move ahead of lending.[12] The estimates should be interpreted with caution as they do not provide an accurate picture of the current financial cycle. Therefore, the Council uses two different estimates to take model uncertainty into account. In addition, the end of the data period is associated with some uncertainty, the so-called end-point problems. However, the method applied reduces this uncertainty.[13]

[1] See the Council's method paper on setting the buffer rate (link).

[2] See 'Frequently asked questions and answers' (link).

[3] The institutions must meet the countercyclical capital buffer requirement with Common Equity Tier 1 capital.

[4] This figure covers the excess capital adequacy relative to the institutions' solvency needs and combined buffer requirements, where the current countercyclical buffer rate of 0 per cent is applicable.

[5] In addition to the countercyclical capital buffer, the total capital buffer requirement in Denmark consists of the so-called capital conservation buffer for all institutions and a SIFI buffer for the systemically important institutions, the so-called SIFIs.

[6] Experience from Denmark shows that the increased capital requirements introduced as part of the international regulation after the financial crisis have not resulted in a decline in lending, see Brian Liltoft Andreasen and Pia Mølgaard, Capital requirements for banks – myths and facts, Danmarks Nationalbank Analysis, no. 8, June 2018.

[7] See also the Council's method paper on the countercyclical capital buffer (link).

[8] The categories are described in the Council's method paper on the countercyclical capital buffer, see www.risikoraad.dk.

[9] In principle, the buffer guide must function as a common basis for when the buffer is to be activated and for the level of the buffer rate. To avoid 'inaction bias', the credit-to-GDP gap and the buffer guide came to play a central role in international recommendations and legislation on the countercyclical capital buffer. It also follows from the recommendations and legislation that decisions on the buffer rate are not only to be based on the buffer guide, but that other quantitative and qualitative information should be included and published. See the source references to recommendations and legislation in the Council's method paper on the countercyclical capital buffer at www.risikoraad.dk.

[10] The buffer guide is currently 0 per cent. According to the mechanical calculation, it will only turn positive when the credit-to-GDP gap is higher than 2 percentage points. The credit-to-GDP gap is shown in the chart pack in chart A4 (right).

[11] See, for example, European Systemic Risk Board, A Review of Macroprudential Policy in the EU in 2017, April 2018.

[12] See Oliver Juhler Grinderslev, Paul Lassenius Kramp, Anders Kronborg & Jesper Pedersen, Financial Cycles: What are they and what do they look like in Denmark?, Danmarks Nationalbank Working Paper, no. 115, June 2017.

[13] See the addendum on page 54 in Grinderslev et al., Financial Cycles: What are they and what do they look like in Denmark?, Danmarks Nationalbank Working Paper, no. 115, June 2017.